Click for Related Articles

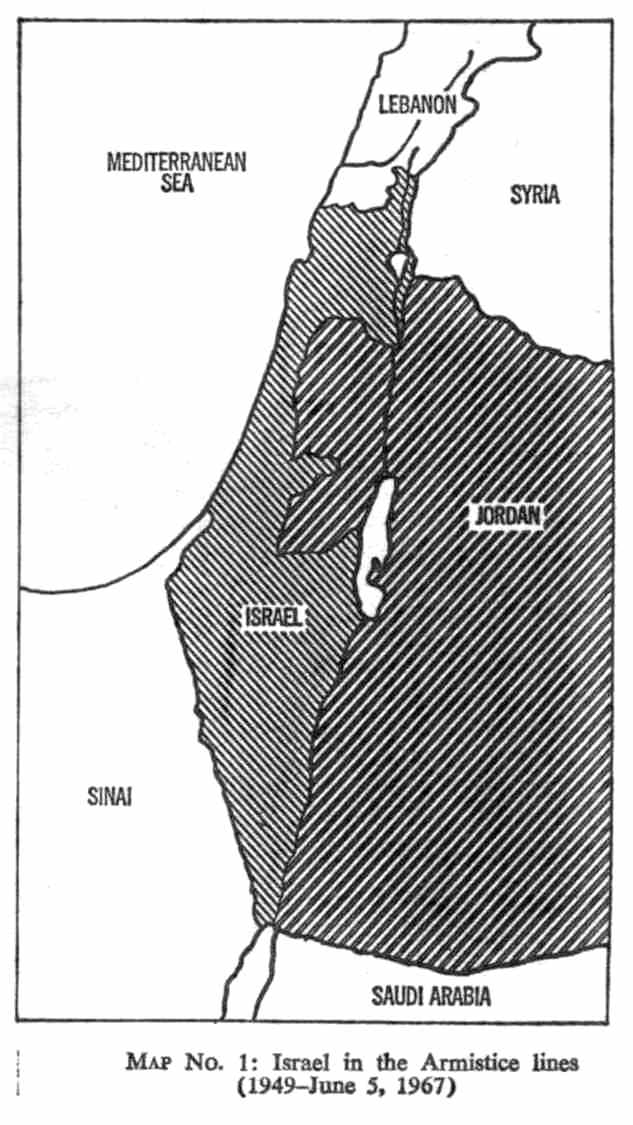

The War before the Six Day WarOn May 14, 1967, the territorial limits of the State of Israel were the lines agreed upon in her Armistice Agreements of 1949 with Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt. Israel held none of the territories she was to gain as a result of the still undreamed-of war three weeks away.

No more vulnerable boundaries could be imagined (see Map No. 1). Along its middle strip, on the Mediterranean coast, the country was nowhere more than ten miles wide. Within this narrow waist were crowded the main centres of the Israeli population: Tel Aviv, with its smaller sister towns Ramat Gan and Petah Tiqva to the east, Bat Yam and Holon to the south, Herzliya and Natanya to the north. These formed its main commercial concentrations and most of its industry. Overlooking the strip from the east was the central range of Palestine's mountains -- the mountains of Ephraim -- and holding these mountains were the Arabs of the Kingdom of Jordan. This central area of the State of Israel could be raked with shellfire, clear through from border to border, without a single gun having to be moved across the frontier. In the early morning of June 6, 1967, a shell fired from the Arab village of Kalkilieh, beyond the northeastern corner of the coastal strip, sailed southwestward through half its length and all its width and exploded half a mile from the Mediterranean beach in an apartment near Masaryk Square in Tel Aviv. In the northeastern section of the state, the Huleh plain, reclaimed from the swamp, dotted with Israelís green villages, lay flat as a billiard table under the stark overhang of the Golan Heights -- and the heights were held by the Arabs of Syria. In the south-western sector, the Sinai Desert, though almost empty of population, was nevertheless well provided with Egyptian military airfields, within three to ten minutes' flying time from Israel's densely populated coastal strip. It was from these frontiers that on June 5, 1967, Israel launched her air force and her army against the Egyptian armed forces, subsequently resisted the invading forces from Jordan and Syria, defeated them all, and gained control of the remainder of western Palestine clear to the Jordan River, of the Golan Heights, and of the Sinai Peninsula down to the Suez Canal and the Red Sea. It is to those frontiers of June 5, 1967 -- to be precise, the Armistice lines of 1949 -- "with minor insubstantial modifications," that Israel has since then been called on to return, even by some of her friends. The pressures suggest that such a withdrawal -- from Sinai and the Gaza district to the gates of Ashkelon, from Samaria and Judea back to the ten-mile-wide coastal strip -- and the restoration to Syria of the Golan Heights above the Huleh Valley -- will bring peace between Israel and the Arab states. The way to peace, it is implied, lies in restoring the conditions that existed before June 5, 1967. The central fact in the life of Israel in the period before June 5 was that in those restricted and confined and frighteningly fragile frontiers the Arab states threatened, planned, and tried to destroy her. It was against Israel in those borders that on May 14, 1967, the neighbouring Arab states -- Egypt, and after her Syria and Jordan, with some support from Iraq -- began massing their forces and their resources to prepare for an imminent onslaught on Israel from three sides. In simultaneous action, they set in motion all the available means of communication with the world at large to make known Israel's forthcoming annihilation. Israel saved herself from that threat and that purpose by the only strategy feasible in her topographical circumstances: a preventive attack on the forces of Egypt, the main enemy. The battles that followed on three fronts, for all their startling, spectacular, even historic success, cost Israel in six days twice as many dead in proportion to her total population as the United States lost in eight years of fighting in Vietnam. The offensive that took shape in Arab minds and began to emerge in May 1967 was the climax-in-deed, the grand finale-of eighteen years of hostilities against Israel on every front except the direct confrontation of the military battlefield. During those eighteen years, the various hostile acts of the Arab states broke every relevant paragraph in the Armistice Agreements of 1949, which all the states had negotiated and signed and which theoretically governed their relations with Israel. Who today remembers a ship called Rimfrost? Or Franca Maria, or Captain Manolls? Who remembers Inge Toft and Astypalea? The sailors who manned them, no doubt, and the merchants whose cargoes they carried. In the 1950s they, and many others like them, were actors in the drama of the continuing and all-embracing Arab attack on Israel. The Inge Toft, a Danish ship carrying an Israeli cargo of phosphates and cement, was arrested in the Suez Canal in May 1959. She was detained for 262 days, until her owners, despairing of their legal rights, ordered the captain to submit to the demands of the Egyptian authorities. The captain released the cargo, and the Egyptians confiscated it. The Inge Toft sailed back to Haifa with emptied holds. In those 262 days, many protests were made in direct communications to Cairo and in debates in the United Nations Assembly against Egypt's flagrant violation of international rights and decisions. None, had any effect. By sending a Danish ship through the Suez Canal, the Israeli government was in fact retreating from a defence of Israel's absolute right to send her own ships freely through the Canal. For eight years, Egypt had forcibly prevented Israeli ships from doing so. International advice -- in fact the urgings of the Secretary General of the UN -- had prompted Israel's government to try the compromise of sending an Israeli cargo on a non-Israeli ship. While the imprisoned Inge Toft continued to demonstrate daily that the Egyptian government would not allow an Israeli cargo through even when carried on a non-Israeli vessel, new advice was forthcoming. The Secretary General of the United Nations, Dag Hammarskjold, informed the Israeli government that he had reason to believe that if, now, on a non-Israeli ship they were to send a non-Israeli cargo- that is, an FOB cargo already the property of the non-Israeli buyer -- Egyptian President Nasser would show what was described as moderation and allow the ships through the Canal. This proposal was accepted by the Israeli government, which even agreed to keeping the transaction secret. The Inge Toft was thus still in detention when, on December 17, 1959, the Greek vessel Astypalea, carrying an FOB cargo, sailed into the Suez Canal. She was promptly arrested and detained. After four months of international protests, her owners also submitted to the Egyptians' demands and allowed the cargo to be confiscated. In the tense months of diplomatic and undiplomatic struggle over these ships, most of the world's maritime powers protested volubly and often. Their own ships, however, continued to sail freely through the Canal. Egypt was thus given daily, even hourly, assurance that, except for name calling, she need fear no reprisals, no punitive or even admonitory action for violating the famous, hitherto sacrosanct and unequivocal Constantinople Convention of 1888. That international compact laid down that: The closing of the Suez Canal to Israel was one detail of the economic war which the Arab states pursued with unrelenting ferocity ever since the State of Israel was established. After signing the 1949 Armistice Agreements, in which they forswore "any warlike or hostile acts," they progressively broadened the scope and deepened the intensity of an all-embracing range of economic hostilities. The Arab states tried to starve Israel of water. First they refused to co-operate in an American -- sponsored scheme for regional exploitation of the sources of the Jordan. Next they tried by force -- employing artillery -- to interfere with Israel's own efforts to realise her meagre water resources (by diverting that part of the Jordan River that ran within her territory). Indeed, because the water shortage was a built-in weakness of Israel's economic structure, throughout those years the Arabs saw Israelís water supply as a prime target for their offensive. The Arab boycott of Israeli goods and services had been launched against the Palestine Jewish community even before the State of Israel was created, and it developed from year to year. In the Arab countries themselves, all commercial relationships with Israel were forbidden on pain of heavy penalties. In fact, any contact whatever with Israel was prohibited. The governments enforced the suspension of all postal, telephone, and telegraph facilities for communications with Israel and prohibited all communication by sea, air, and rail. Any traveller whose passport showed that he had at any time been in Israel, or intended going to Israel, was refused admission to any Arab state. The boycott was extended to every corner of the world. A vast machine saw to its organisation and operation. Over the years, the central boycott office in Damascus compiled a long blacklist of firms the world over who traded with or in Israel, of ships that called at Israeli ports, even of actors or musicians who visited Israel or expressed friendship for Israel. From Damascus a campaign of pressure, threatening blackmail or coercion, was directed at all of them. Questionnaires and admonitory letters were sent to large numbers of firms in many countries to impress upon them that they would not be allowed to do business with the states of the Arab League if they tried to do business with Israel. In Damascus, a world-wide network of inspection was also developed to detect breaches of the boycott. This campaign met with substantial success. The Arab states, with their 100 million potential customers, exercised considerable appeal to manufacturers and merchants hungry for markets. In some of them, soaring oil production had brought about a steep increase in the citizens' spending power. Many firms throughout the world consequently succumbed to the demands, or threats, of the Arab states and quietly joined in the boycott of Israel. The tactics of economic warfare were early extended into every phase of international intercourse and activity, and to the utmost extremity. Planes touching at an Israeli airport were forbidden to fly over Arab territory; they would ask in vain for flight information or even rescue services from an Arab airport. The Arab states refused to co-operate with Israel in any international agency or operation whatsoever, including regional health operations, the war against locusts, the war against narcotics. Economic warfare carried on day in, day out was the unchanging accompaniment to the military and paramilitary siege warfare which Egypt, Jordan, and Syria waged almost incessantly against Israel. Only for two of the eighteen years governed by the Armistice Agreements did Israel enjoy comparative peace with her neighbours. Between 1949, the year of the Armistice, and 1956, attacks from Sinai and the Gaza area, from across the Jordan and down from the Golan Heights, became more frequent and more intense; they were directed mainly at civilians and civilian targets. In that seven-year-period, the Arabs carried out 11,873 acts of sabotage and murder. Israel suffered 1,335 casualties; of these, over 1,000 were civilians. In 1956, the campaign reached a climax. Suddenly the Egyptian government blockaded the Straits of Tiran, the only approach to Israel's southern port of Eilat. On Sanafir and Tiran -- two tiny, otherwise unused islands in the Straits -- they installed gun emplacements. From these, Egypt could straddle and control the southern gateway to Israel, which was thus cut off from direct contact with the southern hemisphere, with the east coast of Africa, and with the Far East. Now, too, armed Egyptian raids into Israel became a daily occurrence. The infiltrators grew ever bolder. From short penetrations across the border, they developed a longer reach into the heart of the country. Individual acts of terror were carried out at the very gates of Tel Aviv. Then, in the early autumn, convoys of Egyptian tanks began to cross the Suez Canal into the Sinai Peninsula. A front line took shape in the desert along the demarcation lines with Israel and in the Gaza Strip, and behind the front line there was a mass of new armour. The tanks gave concrete expression to the purposeful entry of a new element into the arena: the Soviet Union. In 1955, Moscow had begun sending into Egypt tanks and guns and planes in quantities unknown in the area since the major battles in the Western Desert during the Second World War. With these preliminaries in train, the Egyptian government now reached agreement with Jordan, Syria, and Iraq for setting up a joint command. In an atmosphere of high expectation, they prepared for the invasion of Israel. The Israeli Army forestalled them. At the end of October, in a swift campaign, it forced the Egyptian Army back across the Suez Canal into Egypt, eliminated the offensive bases of the infiltrators, and reopened the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping. But the United States government, displaying -- not for the first time -- considerable misapprehension of Arab purposes and the Arab character and a less understandable failure to grasp the elements of Soviet imperialistic strategy, bore down on Israel with heavy diplomatic pressure and the veiled threat of punitive economic action.[1] Israel's government succumbed, and its army drew back from Sinai and the Gaza plain. United States pressure was accompanied at the United Nations by undertakings, seconded by France and Britain and other maritime powers, that they would assure Israel's freedom of navigation in the Straits. There were even promises, though more nebulous, from Washington to assure Israel's right of navigation in the Suez Canal. (When the time of trial came in May 1967, none of these promises was kept.) [1] The attitude of the United States was perhaps determined by its anger at the parallel attack on Egypt launched by Britain and France on their own in reprisal for Egypt's nationalisation of the Suez Canal Company. Both countries had collaborated with Israel. This broad subject does not, however, affect the realities of the Egyptian designs on Israel. Yet the swift defeat in battle had battered and demoralised the Egyptian Army. A large part of its armour and equipment was destroyed or captured. Then came two years of comparative tranquillity. It was not long before the Soviet Union invited Egypt to submit specifications of the arms and equipment needed to replenish her armed strength. The flow of tanks and planes and guns from the Black Sea ports to Egypt was renewed. Later, the Soviet Union began to supply arms in even more pronounced exclusivity to Syria as well. Thenceforward, Egypt's and Syria's relations with the Soviet Union grew increasingly close. The flow of arms grew ever greater. The Arab campaign of violence was resumed in 1959 and never relaxed thereafter. Across the various Armistice lines (except that with Lebanon), Israel was under constant attack: from Jordan-held territory in the heart of western Palestine, from the Gaza plain and Sinai, and from the Golan Heights to the northeast. Tension and harassment were Israel's daily bread. Especially popular with the Arabs were the artillery bombardments from the sheer bluffs of the Golan Heights on the Israeli villages below. There are hundreds of young people in Israel today, born in proximity to the Armistice lines of 1949, who spent most of the nights of their childhood, and many of their daylight hours, in underground shelters. From time to time, the Israeli Army carried out retaliatory raids, on the principle of accumulative retribution. It usually succeeded in halting the Arab belligerence temporarily, but it could not stop it altogether. The full significance of Israel's vulnerability was made manifest suddenly, and to almost universal surprise, in May 1967. Ostensibly, everybody knew that Egypt was capable of turning Sinai into a vast offensive base threatening the very heart of the Jewish state. Ostensibly, it was common knowledge that the United Nations Observer Force, set up in 1957 after the Sinai campaign, would evaporate if Egypt decided to attack. Ostensibly, it was common knowledge that at a moment of destructive exhilaration the Arab states might be capable of united action, forcing a war on three fronts against an Israel outmanned, outgunned, and outnumbered in planes by nearly three to one and in tanks by more than three to one. These elementary facts were largely ignored even by many people in Israel itself -- just as, since the war, Israel has been pressed to forget them again. The facts became clear in quick succession. On May 14, President Nasser started moving his troops and tanks into Sinai. Three days later, the Syrians announced that their forces on the Golan Heights were also ready for action. On the same day, Nasser demanded the immediate withdrawal of the United Nations force from Sinai. The UN Secretary General, U. Thant, promptly complied; the United Nations force disappeared. Simultaneously, the Commander of the Egyptian forces in Sinai, General Murtagi, issued an Order of the Day. For greater effect it was broadcast on Cairo Radio on May 18, 1967: Believing in the power of their numbers, in their unity, and in their ability to exploit Israel's glaring strategic weakness, the Arabic leaders and spokesmen now articulated the simple objective of their policy and their labours: annihilation of the Jewish state. The Arab leaders, as it turned out, had miscalculated. They were, it is true, united; they did outnumber the Israelis heavily, in men, planes, tanks, guns, and ships; if they had been able to exploit these conditions, Israel's topographical weakness could have been fatal to her. Israel is now being asked (or told, or cajoled) to resume that topographical weakness, or that topographical weakness with, in the words of the United States government, "insubstantial modifications." The Arabs' war against Israel in the years between 1949 and 1967 was accompanied and dramatised by an incessant diplomatic offensive and a campaign of propaganda that grew progressively in volume and scope. Its purpose was not kept secret. It was -repeated again and again. "Our aim," it was epitomised by Nasser on November 18, 1965, "is the full restoration of the rights of the Palestinian people. In other words, we aim at the destruction of the State of Israel. The immediate aim: perfection of Arab military might. The national aim: the eradication of Israel." Year after year, the autumn sessions of the United Nations in New York were converted into a sounding board for the combined verbal onslaught on Israel of the delegates of the ever-growing number of Arab states. The war against Israel on its many fronts

was pursued against an Israel that did not embrace the "occupied territories"

of today. At that time, too, Israel was pressed and urged from many sides

to make concessions. What could these concessions have been? In those years,

too, Israel was pressed to offer concessions of "territory." But it was

the Arab refugee problem that was named as the prime cause of Arab intransigence,

as the

fons et origo of all the trouble in the Middle East. That

was then proclaimed the major obstacle to peace.

This page was produced by Joseph

E. Katz

Source: "Battleground: Fact & Fantasy

in Palestine" by Samuel Katz,

|

All rights reserved. Reprinted by Permission.

Portions Copyright © 2001 Joseph Katz