Oriental Zionism of Arab-born Jews,

One thousand years before Theodore Herzl

My heart is in the East and

I am at the

uttermost West.

-Judah Halevi, 1086-1141

The mode of conducting Jewish affairs

among themselves ... is entirely

in Hebrew, which ancient custom

they are very tenacious of and

desirous to maintain.

-W. T. Young, British Consul in Jerusalem,

1839

Clearly the massive exodus of Jewish

refugees from the Arab countries was triggered largely by the Arabs' own

Nazi-like bursts of brutality, which had become the lot of the Jewish communities.

Walter Laqueur writes: "History has always shown that ... men and women

have chosen to leave their native country only when facing intolerable

pressure."[1] But the history is long of persecution against Jews by the

Arabs, a chronicle of "intolerable pressure" that had its beginnings in

and took its inspiration from the seventh-century book of the creator of

Islam.

History has also illustrated that persecution

and its pressures become "intolerable" only when an alternative other than

death is provided. The Arab-bom Jews suffered in silence until they learned

that they could act out their hope of getting to a Jewish state.

They bore their burdens as did many peoples

of the world before and until the United States became the universal haven

of the oppressed. Yet the hapless black peoples who had been brought to

America as slaves could not even begin to alleviate their oppression

and exploitation here until they began to gain the freedoms and thus the

strength to resist and insist upon their rights-rights that are in some

areas yet to be achieved.

There is no doubt that the long-sought

Jewish national homeland was finally brought into being by a horrified,

conscience-stricken international community, which viewed Israel as a necessary

refuge for Jews throughout the world who had become victims of the Nazis

or their followers. However, after World - War I, in 1918, nearly half

of the total Jewish population in Jerusalem- consisted of "Sephardic" Jews

-- that is, the Jews of the Middle East, non-European Jewry.[2] And it

cannot be denied that the overwhelming majority of hundreds of thousands

of Jewish refugees fleeing from Arab persecution also poured directly into

Israel -- in fulfillment of an unflagging, little-known "Zionism," a national

liberation movement among Arab-born Jews whose gestation period had lasted

roughly two thousand years.

From the Arab conquest, hundreds of thousands

of Jews in the Arab world managed to survive between traditional ravages.

Most had religious affiliations. The-Arabs' general prohibition against

political activities by their Jewish

dhimmis

might have been a factor

that inhibited and submerged the growth of Zionism as a political phenomenon

among the Sephardic Jews. But what may be called "spiritual Zionism" took

root in biblical times in the Sephardic Jewish community; those Jews, who

are uniquely indigenous to the terrain that now is the Arab world, have

retained in their liturgy the steady longing for "return" to the Land of

Israel, a longing that has been mistakenly assumed to be exclusively "European."

Jews from Arab countries often become incensed

when confronted with the argument that Zionism originated in Europe. Every

Sephardic Jew interviewed had the same immediate reaction: the Sephardim

are just as truly believers in Zion, and their ancient uninterrupted Jewish

history led directly from the destruction of the Temple at Jerusalem.

They too were descendants of the original

exiles, and, unlike their Western Jewish brothers, their empathy with the

Bible was not dependent upon "unyielding interpretations," because Sephardic

Jews lived in close proximity to the world of the Bible and could more

easily relate to it. During an interview with an eminent Jewish scholar

from Tunisia, I mistakenly likened the Sephardic Jewish communities, which

have burgeoned in Israel and elsewhere since the Jews' exodus from Arab

countries, to the European "shtetl." The scholar promptly corrected

that assumption, somewhat bitterly and with alacrity. He explained that

They are more like our own "mellah

"

or "hara, " which many people probably never heard of. Zionism was

in the Arab countries with every prayer we uttered for millennia before

Herzl.

Sephardic Zionism

Nearly every one of the recurrent "false Messiahs"

who attempted to play the Messianic role in leading the Jewish people back

to Israel were apparently Sephardic Jews.[27] One Messianic movement was

started by two Sephardic Jews who attempted to negotiate with the Pope

in 1524. When they failed to convince him of a plan that would liberate

Palestine for the Jews, another proposal was made to the German emperor,

Charles V, after which both would-be Messiahs were arrested and jailed.[28]

One, Solomon Molcho, was burned to death, "a martyr's death," and the other,

David Reubeni, "a mysterious character," disappeared, leaving his diary

behind.[29]

Shabbetai Zevi, who along with his prophet,

Nathan of Gaza, is considered son of "Mordechai of Smyrna." Zevi's followers

came from "Amsterdam to Yemen, from the eastern frontier of Poland to the

outlying villages in the Atlas Mountains of North Africa." His unparalleled

ability to lead the receptive Jewish people "back" was attributed by Gershom

Scholem, the foremost authority on Zevi and his Sabbatean movement, to

"the general atmosphere within Jewry," which was "more decisive in shaping

the movement than the peculiar spiritual state of the youthful ... Sabbatai

Sevi."[30] Because the seventeenth century was fraught with persecution

for both Sephardic and Western (Ashkenazic) Jews, "penitents and seekers

of liberty-rich and poor, scholars and the ignorant-thus united round"

the Messianic movement.

It was Zevi himself who was the "weakest

of its leaders" -- "in 1666 ... the Jews who saw him entering the sultan's

palace" never dreamed that "the messiah had adopted ... Islam." But Zevi

had done exactly that, upon "being threatened with great physical punishment

and even death." Because of Zevi's conversion, one writer says that "The

greater part of Jewry was shaken to the core. The blow was even greater

than the crucifixion of Jesus had been to his followers."[31] The disillusionment

was shattering; "Jesus had paid the highest price that could be demanded

from a man, but Shabbetai had not."[32] Zevi "fell into a state of deep

depression" after his conversion, then recovered and "went wandering from

community to community, preaching . . ." and committing "strange actions"

afterward. The letter of renunciation of his former visions, which Zevi

had been "compelled" by a "strict rabbinical court" to sign in Venice two

years after his conversion, remained intact:[33]

Although I have declared that

I saw the Merkava as Ezekiel the prophet saw it and the prophecy

declared that Shabbetai Zevi is the Messiah, the Rabbis and Geonim of Venice

have ruled that I am in error and there was nothing real in that vision.

I have therefore admitted their words and say that what I prophesied regarding

Shabbetai Zevi has no substance.[34]

Shabbetai Zevi died at fifty in 1676.

Another prominent Sephardic Zionist was

Spanish-bom Rabbi Manasseh ben Israel, a major seventeenth-century Jewish

scholar. Rabbi ben Israel became convinced that England -- which had no

Jewish population for three hundred years -- was holding back the redemption

and return to the Holy Land. The horror of the Spanish Inquisition, he

maintained, had fulfilled part of the biblical requisite -- the suffering

-- but the Bible had promised to restore the Jews to Israel only after

they had also been dispersed to every part of the world.

Since ben Israel had ascertained that some

settlers in America were Jewish, he concluded that only England-bereft

of Jews-stood in the way of "return." In a formal "declaration" to the

British, he explained that " . . . before the Messiah come ... first we

must have our seat here likewise." For good measure, he strengthened his

argument by stressing the economic benefits England could derive through

imports and exports from Jewish merchants throughout the world. The British

may have considered other factors more determinative, but some historians

credit Rabbi ben Israel as the direct force that brought about the re-entry

of the Jews to England.[35]

There have been Sephardic Jewish "Zionists"

from the time of the biblical exile of the Jews from Jerusalem in 586 B.C.

"It is common knowledge that religious life in the Diaspora was bound up

with the Holy Land and with the Temple so long as it existed. The connection

of Cyrene, Carthage and the rest of North Africa with Palestine was in

fact quite strong."[36]

"Jason of Cyrene" wrote a five-volume work

about Palestine, where he arrived during the Hasmonean Revolt." The pilgrimages

to Jerusalem by Libyan Jews were recorded in the Bible," as was the Jerusalem

synagogue that was named after them." "Simon the Cyrenian" was one of many

of the Libyan pilgrims who remained in Jerusalem. It was Simon who was

reported by the New Testament to have been " a chance passerby just arrived

from the country," who "was forced to take part in the crucifixion."[40]

The holiday of Passover, commemorating

the Jews' return from exile in Egypt to the Holy Land of Israel, was not

celebrated differently by eleventh-century "Palestinian Jews" than by modem

Jews around the world. It was when the Jews left Egypt, no longer slaves,

that they became organized-a people with the prospect of returning to their

land.[41] Passover service for Jews everywhere concludes with the words,

"Next year in Jerusalem." Sephardic clergy explain rather impatiently that

the basic Sephardic liturgy is "much the same" as the European, although

the Sephardim are particularly proud of the indigenous poetry that enhances

their religious literature.

In fact, much of the universal Jewish liturgical

devotion to the Holy Land has been adopted from.Sephardic-Jewish scholars.

An important example is venerated twelfth-century rabbinical scholar

and poet, Jehudah Halevi, whose words became a prominent part of the universal

Jewish liturgy -- "My heart is in the East and I at the uttermost West

. . ." and "Ode to Zion,"[42] among others.

Halevi was also a pragmatist who wrote

serious treatises on the theme that became the foundation of modern Zionism

-- rather than languish in exile, he stressed, the Jews themselves must

take the first step and the Messiah would come later. Faithful to

his enjoinder, Halevi left his thriving family and career as physician,

and set out from Spain in the twelfth century on what was then the hazardous

journey to Palestine.

Halevi was warned by friends and compatriots

when he broke journey in Egypt, according to his German biographies. But

after resting, he resisted their attempts to dissuade him from continuing:

"In Egypt, Providence showed itself in a hurry as it were; it settled down

permanently in the Holy Land only," Halevi wrote. His German biographer

likened Goethe's Faust to Halevi's "highest moment"-"when he first set

eyes on the Holy City, as it came into his view between the mountains."

Halevi "wanted to walk barefooted over the heap of ruins that had once

been the Temple." According to traditional history, he had barely arrived

at the gates of Jerusalem and was kissing the stones of hallowed land,

when he was slain by an Arab tribesman.[43]

The concept of the "return" of the Jews

from exile to the biblical homeland in Zion-the promised land-was an integral

part of Jewish life everywhere, but nowhere was it more fervently held

or more inextricably interwoven with daily life and long-range hope than

among the Sephardim. They were intense in their religious observances.

Some of the most perceptive and distinguished Jewish scholars came from

"Arab" countries, and the revered Babylonian Talmud was compiled in what

is now Iraq. The Sephardic Jews were diligent in their religious pursuits,

and would have disdained any open attempt to deviate from the flexible

norm of religious observance. The synagogues in many haras or mellahs were

the hub of social life as well as a moral duty.

Jewish communities were tightly knit, and

their interpersonal relationships attained the close warmth of an extended

family. They spoke their prayers with understanding and expectation of

eventual

fulfillment. Their implorations for deliverance from the austerity of exile

in foreign lands, and the promised ingathering of the Jews back in the

Holy Land was, for many of them, not mere cant recited by rote, but a sincere

profession of anticipation and desire.

Scattered throughout the vast extent of

what became the Arab world, and isolated within it during all the centuries

of harsh Arab rule that came after their exile, the Sephardic Jews looked

forward to this realization of a prophecy. Although from time to time manifested

in the temporary acceptance of one Messianic pretender or another who would

lead them back to Zion, the eventual debunking of these self-anointed zealots

did not diminish hope.

Their synagogues, as every synagogue in

the world theoretically, were constructed so that the worshiper would be

directed toward Jerusalem -- when he entered, upon facing the Torah (holy

scrolls), and when he or she stood to pray."[44] Even in the most isolated

Jewish troglodyte communities of southern Tunisia or the remote island

of Djerba, the prayers which were offered were much the same as those in

the services of a modern American synagogue.[45] Whether said three times

a day, as prescribed by pre-eminent religious Jewish scholars in Arab and

European countries alike, or recited at dawn and sunset-when the Tunisian

Jews from troglodyte villages around Matmata[46] came out of their limestone

caves to pray-the prayers always[47] included the plea to

... Sound the great Shofar for

our freedom; ... bring our exiles together and assemble us from the four

comers of the earth. Blessed art thou, 0 Lord, who gatherest the dispersed

of thy people Israel to return in mercy to the city Jerusa lem; ... rebuild

it soon, in our days.... Blessed art thou, 0 Lord, Builder of Jerusalem.[48]

Perhaps the most unfortunate among the Jews

in Arab countries took their prayers more literally than the relatively

secure. Many orthodox Jewish victims of Euronean nersecution also turned

inward toward hope of redemption, while many others observed fewer symbolic

traditions -- European Jewish citizens who obstinately believed themselves

"assimilated" up until the decree of a death sentence by Hitler's Nuremberg

Laws or their precursors. But for the Jews in the Arab Muslim world, "assimilation"

was a contradiction in terms, as impossible in the twentieth century as

it had been a thousand years before.

For virtually all Sephardic Jews, religious

life was active, and was integrally connected to the "Palestinian center."[49]

Because Jerusalem had been sacred to Jews fifteen centuries before the

Prophet Muhammad was born -- just as Mecca and Medina are sacred to Muslims

because the Prophet Muhammad lived and worked there"--over the centuries

the dispersed Oriental Jews sent offerings to Jerusalem. There a Jewish

center had been established near the "Western" or "Wailing Wall," the sacred

ruin at the site of the original Temple built by King Solomon, and the

site too of the Jews' Second Temple that the Romans had destroyed in A.D.

70.

Though the Jewish refugees from Arab lands

in the twentieth century had no international multigovernment assistance

agency, as the Arab refugees have had UNRWA, the latter-day outpouring

of Jewish funds to modem Israel for its refugees stemmed from an ancient

tradition. Historian S. D. Goitein tells of the disgrace that befell an

eleventh-century Tunisian Jewish community because it had failed to make

its "annual appeal for the Academy of Jerusalem" promptly. However, the

community "assures us that the Jerusalem appeal was carried through....

albeit belatedly," and thus, redeemed itself.

As an amusing example of the geographical

diversity of "Palestine's" jurisdiction over the Jews in Diaspora,

A Jewish court in India . . .

issues, in the year 1132, a [proprietary] document for a local girl and

a merchant from Tunisia in the name of exilarch of Baghdad and of the Palestinian

Gaon [Chief Rabbi], who at that time had his seat at Cairo.*[51]

Jewish schools in the Mediterranean Diaspora

prayed for the "welfare of dedicated community leaders at the holy places

in Jerusalem.'[52] The "synagogue of the Palestinians,"* which described

itself in legal documents as "acting on behalf of the High Court of the

yeshiva [academy] of Jerusalem and its head . . ."[53] was the main

synagogue of Old Cairo, Alexandria, Ramle, Damascus, and Aleppo in the

eleventh century, Documents have been found attesting to Jewish cultural

and spiritual life in a "sizeable" fourteenth-century Jewish community

at Bilbays, a town "on the caravan route from Cairo to Palestine," even

after it had been subjected to forced conversion to Islam en masse, and

its synagogue turned into a mosque.[54]

[* The centuries-old traditional use of

the term "Palestinian" to describe Jews provides forceful repudiation of

the present popular usage of "Palestinian" -- to denote exclusively the

Arab refugees. The psychological propaganda benefit derived by the Arabs

from annexing the word "Palestinian," to designate only Arabs, is considerable:

if the Arab refugees are seen as the "Palestinians," the world reaction

becomes conditioned to identifying the Arab "Palestinian" refugees with

Palestine. Although the greatest bulk of Palestine is known today as Jordan,

this fact has become obscured. There appears today no popularly known "Palestine"

except the smaller area which became Israel, so the perceived connection

between Arab Palestinian refugees and Israel will follow. Thus, the misstatement

now in common use: "Palestine became Israel." See Chapters 8 and 12.]

Pilgrimages such as Rabbi Halevi's or Maimonides'

were frequently made with great difficulty from all comers of the Arab

world. And the inspiration for the Spanish-bom Halevi was provided by the

writings of a native of Fez, Morocco, the eleventh-century Rabbi Isaac

Alfassi, who was called "the symbol of Hebrew scholarship in North Africa."[55]

Complaints were in fact registered about the heavy burden of maintaining

the way stations in Egypt's Jewish community, where Jewish pilgrims en

route to the Holy Land "expected to be equipped" for the rest of the arduous

trip.[56]

Documents recording the modern history

of the Jewish national liberation govement give sparse credit to the significant

role of Sephardic Jews' devotion over the centuries to the philosophical

and spiritual nationalism that undoubtedly prepared a base for modem Zionism.

Indeed, a Sephardic Jew, Rabbi Yehudah Alkalay (1798-1878), has been called

the precursor of modem Zionism. Walter Laqueur,[57] in a study dealing

primarily with the European Zionist movement, states: "It should be noted

at least in passing that another rabbi, Yehuda Alkalay, writing in Serbia

... had already drawn up a practical program toward ... the return to Zion";

Sephardic "Zionist" Alkalay's development came twenty years before the

European Zionist whose work Laqueur was discussing.[58]

That some Jews from Arab lands were already

"home" in Alkalay's time is attested to by many recorded visits and foreign

consulate communications. One dispatch from the British Consulate in Jerusalem

in 1839 reported that "the Jews of Algiers and its dependencies, are numerous

in Palestine. . . ."[59] In 1843, a Christian missionary from England wrote

of "the arrival" in Jerusalem of an additional "150 Jews from Algiers,"

and he noted: "There is now a large number of Jews here from the coast

of Africa, who are about to form themselves into a separate congregation.

"[60]

Not only were the Sephardic Jews "numerous"

in the Holy Land, but their Language, Hebrew, was popularly used "in the

ordinary affairs of life" long before the "new Jewish immigration of the

early eighteen-eighties."[61] In 1839 British Consul Young, in Jerusalem,

reported that "the mode of conducting Jewish affairs among themselves ...

is entirely in Hebrew, which ancient custom they are very tenacious of

and desirous to maintain..."[62] Young had found it "necessary" to

hire a Hebrew interpreter "immediately upon his appointment in 1838."[63]

Another British consul, James Finn, in 1850 transmitted the "translalation"

of a Hebrew petition from "the Moghrabi or African Jews settled in Jerusa...

[who] form a considerable body, increasing in numbers..."[64]

In 1862 Finn suggested sending a Hebrew-speaking

member of his staff to "the Jews of Galilee"[65] and he noted in his memoirs

that, "With regard to pure Hebrew, the learned world in Europe is greatly

mistaken in designating this a dead language. In Jerusalem it is a living

tongue of everyday utility." In fact, Hebrew was "spoken" and widely used

in the "English Consulate."[66] His wife, in her own book, Reminiscences

of Elizabeth Anne Finn, related that in everyday life as well as official

business, "all the men spoke Hebrew, and I have seen men from Kabul, India

and Jerusalem, meeting as total strangers, at once fall to conversing in

Hebrew, which was still a thoroughly living language, for speaking as for

literary and religious purposes."[67] Thus, Sephardic "Zionists" found

a "living" Hebrew when they arrived at "The Land."

Simultaneously, non-Jewish "Zionists" were

urging the "regeneration of Palestine" as a Jewish homeland, in part due

to their horror at leaming of the tortures and persecution of the Jews

of Damascus following the blood libel of 1840 In June of 1842 Colonel Charles

Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough's grandson, wrote that, "in his view,

the Jews ought to promote the regeneration of Palestine and the eastern

Mediterranean region. Were they to do so, they would, Churchill believed,

'end by obtaining the sovereignty of at least Palestine.' Charles Churchill

felt strongly that the Jews should resume what he described... as their

'existence as a people.' "[68]

Another non-Jew reportedly espousing the

Jewish nation was Napoleon Bonaparte, who launched his campaign to conquer

Palestine in 1799 with a pledge to "restore the country to the Jews."[69]

While Napoleon was unsuccessful in his attempt, some believe he was a catalyst

for

a distinguished gallery of writers,

clerics, journalists, artists and statesmen [who] accompanied the awakening

of the idea of Jewish restoration in Palestine. Lord Lindsay, Lord Shaftesbury

(the social reformer who learned Hebrew), Lord Palmerston, Disraeli, Lord

Manchester, George Eliot, Holman Hunt, Sir Charles Warren, Hall Caine-all

appear among the many who spoke, wrote, organized support, or put forward

practical projects by which Britain might help the return of the Jewish

people to Palestine. There were some who even urged the British government

to buy Palestine from the Turks to give it to the Jews to rebuild.[70]

Sir George Gawler, who had fought in the battle

of Waterloo, wrote in 1845 that "the most sober and sensible remedy for

the miseries of Asiatic Turkey" was to "Replenish the deserted towns and

fields of Palestine with the energetic people whose warmest affections

are rooted in the soil." Gawler published a series of pamphlets on the

theme, one on "the emancipation of the Jews," and in 1849 he made a pilgrimage

to Palestine with his friend, Jewish leader Sir Moses Montefiore. [71]

In 1847, Lord Lindsay declared his hopes

that

The Jewish race, so wonderfully

preserved, may yet have another stage of national existence opened to them,

may once more obtain possession of their native land.

... The soil of Palestine still enjoys

her sabbaths, and only waits for the return of her banished children, and

the application of industry, commensurate with her agricultural capabilities,

to burst once more into universal luxuriance, and be all that she ever

was in the days of Solomon .[72]

Jewish state took on such popular appeal[73]

that the press repeated false rumors that Lord Beaconsfield -- Benjamin

Disraeli -- had attempted and failed to achieve the restoration of Jewish

Palestine, and asserted that "If he had freed the Holy Land and restored

the Jews, as he might have done instead of pottering about Roumelia and

Afghanistan, he would have died dictator."[74]

Meanwhile, thousands of miles distant,

more than 2,000 Yemenite Jews were setting out on the perilous journey

to their homeland, where they would arrive in 1881. There the "first enduring

Jewish agricultural settlement in modem Palestine" -- Petach Tikvah --

was founded on the "deserted and ruined" Sharon Plain by "old-time" Palestinian

Jewish families who left "the overcrowded Jewish Quarter of the Old City

of Jerusalem" in 1878. It was four years later that what called the first

aliyah

(Hebrew),

a great wave of Jewish European refugees, would settle on the land." Theodor

Herzl came with his own concept of modern Zionism, but not until many years

afterward. In fact, Theodor Herzl's grandfather reportedly attended the

Sephardic Zionist Yehudah Alkalay's synagogue in Semlin, Serbia, and the

two frequently visited. The grandfather "had his hands on" one of the first

copies of Alkalay's 1857 work" prescribing the "return of the Jews to the

Holy Land and renewed glory of Jerusalem." Contemporary scholars conclude

that Herzl's own implementation of modem Zionism was undoubtedly influenced

by that relationship.[77]

Alkalay was subjected to "scornful criticism"

for his unorthodox dream: "that all of Israel should return to the land

of our fathers." Alkalay was perhaps the first to write of the "Damascus

Affair" -- the blood libel of 1840 -- and that episode apparently crystallized

his "daring" ideas. "Complacent dwellers in foreign lands" must be chastened

by the suffering of the Jews in Damascus.[78] Intent upon unifying a worldwide

Jewish coalition for nationhood, in 1874 Alkalay immigrated to Jerusalem

at the age of seventy-six .[78] Although he is cited in some authoritative

chronicles, and anthologies,[79] his achievement remains little-known.

Alkalay and Sephardic Jews in general are given greater cognizance in a

contemporary French study: "From the period of the'golden age' of Spain

to the death of Alkalay ... the contribution of the Sephardim-beyond its

extraordinary cultural influence on Judaism -- to the rebirth of the Jewish

national entity ... resides incontrovertibly in their" overwhelming adoption

of the Jewish state, the intensity of their love for Zion and their unshakeable

belief in the coming of the Messiah."[81]

A dramatic illustration of this point is

the 2,500-year-old Jewish community in Yemen, which in 1948 picked up its

collective self and boarded "the wings of Eagles" to Israel. As discussed

at some length in the last chapter, the Yemenite Jews had remained singularly

adherent to the ancient Jewish tradition despite, or perhaps because of,

the constant persecution and degradation to which they were subjected by

the Arabian Muslims. They seemed still faithful to the reminder that the

venerated philosopher, Maimonides, had written them, in his "Epistle to

Yemen" in 1172:

It is, my coreligionists, one

of the fundamental articles of the faith of Israel, that the future redeemer

of our people will ... gather our nation, assemble our exiles, redeem us

from our degradation, propagate the true religion, and exterminate his

opponents as is clearly stated in Scripture

Remember, my coreligionists, that on account

of the vast number of our sins, God has hurled us in the midst of this

people, the Arabs, who have persecuted us severely, and passed baneful

and discriminatory legislation against us, as Scripture has forewarned

us, "Our enemies themselves shall judge us" (Deut. 32:3 1). Never did a

nation molest, degrade, debase, and hate us as much as they...

Although we were dishonored by them beyond

human endurance, and had to put up with their fabrications, yet we behaved

like him who is depicted by the inspired writer, "But I am as a deaf man,

I hear not, and I am as a dumb man that opens not his mouth" (Ps. 3 8:14).

Similarly our sages instructed us -- to bear the prevarications and preposterousness

of Ishmael in silence .... [82]

The general Sephardic stoicism and steadfast

rejection of conversion to Islam in the face of constant abuse was an impressive

monument to cultural and spiritual Zionism, yet in Yemen this quality was

perhaps most pronounced. There the Jews were poor. The Koran has ordained

"twice" (2:1; 3:112) that Jews be poor. The Muslims in Yemen and other

Muslim countries took the words "literally": "Yemenite Jews ... always

were clothed like beggars ... some of the older generation cling to this

habit even in Israel" and at times "Jewish property, even houses, were

taken away from them" by Muslims because "they presented a picture of wealth

incompatible with the state assigned to the Jews by God."[83] Western culture

had barely penetrated anywhere in Yemen, but Yemenite Jews were extremely

clean, and their pious community sent its children to synagogue at the

age of two. By the time they were three or four, they were learning the

Torah (Jewish law and tradition).

The Yemenite Jews seemed, to those who

visited there, to be waiting, in what they also deemed was their necessarily

miserable exile, for the return to the "Perfect World"[84] -- and, in costume,

they rehearsed the celebration of their redemption on every Sabbath on

which they were not forced to work. Israelis who received the Jews from

Yemen upon their arrival in Israel reported that the deliriously happy

Yemenites could not be dissuaded from referring to the Israeli greeters

as "prophets." Some of them were disappointed that "King David" was not

on hand.

For many more sophisticated Jews from the

Arab centers, the drive toward Israel was based not as strictly on the

mystical or religious aspect of the "return," but on their cultural identification

with a "people." One young Tunisian Jew was described very succinctly in

a study:

His fate ... lies not in his birthplace,

Tunisia, but in his ethnic homeland of Israel. There is no future for him

in Tunisia, whereas in Israel, there is a possibility ... of a great existential

experience. "If I have only one life, I want to dedicate my life to something

greater than me."[85]

When, in the familiar Jewish wedding tradition,

the bridegroom stomps on a glass, the crushed goblet is a reminder of the

destruction of the temple in Jerusalm: nowhere is this observed more passionately

than among Sephardic Jews.

The identification with a Jewish homeland,

a Jewish nationality, remained a strong influence even upon the young Sephardic

Jews, whose education and social life broadened with the liberalizing influence

of non-Arab colonials. In twentieth-century Iraq, for example, during a

period when Turkish rule allowed for many young Jews to expand further

into the intellectual mainstream, there was a break with many elements

inherent in traditional Jewish life. Yet the Iraqi Jews continued to observe

the symbolic traditions; they were still fasting on the Day of Atonement

and "maintaining" various traditions "even in recent years."[86]

Significantly, very few of the Jews whose

day-to-day religious observance has dwindled have converted.[87] The pattern

that has evolved in the latter twentieth century, it seems-although the

regular religious observance has assumed less importance as a daily ritual

than it had for their forebears-is that their ethnic or cultural identification

as "the Jewish people" has stood constant and perhaps even strengthened.

Had the Jews from Arab countries enjoyed the same manifold freedoms and

opportunities that are the right of every citizen from many Western nations,

it is uncertain whether the unprecedented virtual emptying of Jews from

Arab countries would have been precipitated by the re-creation of the Jewish

State. Perhaps they would have continued to adhere to the pattern set by

American Jews, of whom a minuscule percentage have moved to Israel.

The hardships faced by hundreds of thousands

of refugees once they arrived in the embryonic Jewish state were multiple-for

Jews born in Arab countries, a new language, modem Hebrew, had to be learned,

and the swarms of homeless had to be housed. The refugee camps and "temporary"

housing-maabarot-were bulging.

Raphael Patai described some of the conditions

encountered by the hopeful hordes of refugees when they arrived in the

"land of milk and honey":

The great majority of them were

housed in tents which were drenched from above and flooded from below during

the heavy rains of the winter of 1949 and 50. The original plan called

for a sojourn of a few weeks only in the immigrants' camps after which

each immigrant was to be sent to a permanent place of settlement. Actually,

however, in view of the large number of immigrants the rate of evacuation

from the camps lagged constantly behind the rate at which the new immigrants

were brought into Israel, and the period of sojourn in the camps was prolonged

from three months, to four months, to six months, to eight months ...

One of the main immigrant's reception camps

[refugee camps] was that of Rosh Ha'ayin, in which at the height of its

occupancy in 1950 there were some 15,000 Yemenite Jewish immigrants, all

lodged in tents, fifteen of them in each tent. The few buildings in the

camp were used to house the hospital and the clinics.... When the immigrants

arrived many of them were very weak. Mortality was high, and as many as

twenty deaths occurred daily.... very soon, mortality decreased and generally

the strength of the people increased. Practically all the immigrants (98

percent to be exact) suffered from trachoma when they arrived at Rosh Ha'ayin.

After a four months' sojourn in the camp, and constant medical treatment

-- often administered against the wishes of the patients -- this percentage

sank to 20 percent. The health of the children was also in very bad shape.[88]

In 1951, 256,000 Jewish refugees -- or one-fifth

of Israel's population then, which was 1,400,000 -- were still living in

"temporary" settlements.[89] Mordechai Ben Porath, an Iraqi-born Israeli,

and long a member of Israel's Parliament, told of the camps in the '50s:

I arrived in Israel penniless

and, in the early 1950's, directed a transit camp for tens of thousands

of Jews from Arab countries. There my family and I lived with them. I saw

those people housed in makeshift huts without water, without electricity,

exposed to rain, wind, and even flood. Professional people were helpless:

they didn't have their licenses or any other certificates with them. These

had been tom to shreds by Arab officials in certain Arab countries when

they left.[90]

The refugees had little in common with their

brothers who had immigrated to the Holy Land generations before. This was

particularly true of the Yemenite Jews. More than two thousand "Zionists"

from Yemen had managed to get to Palestine in 1881. By the time of the

refugee deluge of 1948 and onward, more than 45,000 Jews from Arab lands

already were living in the country. In fact, relative to the total populations

of Jews in Asia and Africa from 1919 to 1948, more Oriental Jews immigrated

from the East than from Europe and America, with approximately one-third

of Yemenite and Syrian Jews becoming immigrants; "as far as is known, there

was no other Jewish community from which such a high percentage immigrated"

to the land of Israel between 1919 and 1948.[91]

Carl Hermann Voss, a theologian and, in

1953, Chairman of the American Christian Palestine Committee, discussed

the "125% increase of population" during Israel's first five years: "A

difficult adjustment was necessary.... The Israel of 1948 had only meager

natural resources, limited capital, and no friendly states on its borders

.... The fabric of this swiftly growing society was strained by the heterogeneity

of ... the several hundred thousand Oriental Jews who came from Iraq, North

Africa, and Yemen."[92]

Voss wrote of his "memorable experience"

to see Jews

coming home from lands of death

and dispersal to a land of life and light ... a fulfillment of the prophecy

of Isaiah ... for Jews who had left the caverns and cellars of North Africa

or the bleak wastes of feudal Yemen. In a Ma'abara work village on the

slopes of Mt. Carmel not far from Elijah's cave, I talked to a bizarre

type of Jew-a Jew from Baghdad, purportedly descended from those who did

not return with Ezra and Nehemiah from the Babylonian exile to rebuild

the Temple 2,500 years ago. In garb that made him almost seemed incongruous

in this modern setting of the new Israel; yet this Iraqi Jew gave new meaning

to a sentence I had learned in my youth: "Behold I shall bring them from

the north country and I shall gather them from the coasts of the earth.

A great company shall return thither."[93]

For Jews born in Arab countries, the many

freedoms in Israel often had to learned. One poignant scene was described

by historian Goitein, who visited refugee way-station camp in Aden, where

Jews fleeing from Yemen were waiting get to Israel.

[It was] in the receiving camp

of Hashid near Aden in November 1949. The scene occurred between two Yemenites,

one an Israeli, a man who had lived in Palestine long enough to become

socially naturalized, and the other an immigrant who had arrived at the

camp only a few days previously.

The Israeli Yemenite, an attendant working

in the camp, of course mixed on terms of complete equality with everyone,

else there, with the director of the camp, the chief doctor and with a

university professor. One day I was standing near him when an immigrant

Yemenite ran up to him and in a fraction of a second threw himself on the

ground before the attendant, kissing his feet and embracing his legs, while

making some trivial request. The mere physical aspect was quite remarkable.

Throwing oneself down on the ground with such force without getting hurt

showed that the man must have had long practice in such matters. Yemen

is, of course, one of the more backward Arab countries; still, that unforgettable

little scene illustrates a tremendous contrast."[94]

There are Jews who sought refuge from Arab

countries, who are dedicated to their Jewish homeland, but who retain many

happy memories of their lives in the very communities from which they fled.

Yet during long conversations, as they recalled the past, these people

from different Arab lands related individual experiences so similar in

their discriminatory character that, despite their distances from one another,

they seemed to speak in unison. Although they never had met and probably

never would meet, they narrated a collective chronicle of a buoyant, resilient,

close-knit community life punctuated by fear and demeanment, and by intermittent

terrorizing and anti-Jewish violence.

Their ambivalent remembrances indicated

a kind of nostalgia for the land and customs of their origin and childhood.

For some, the nostalgic tendency is enhanced by the passage of time and

tempered by dissatisfaction at the frequent conditions of austerity and

hardship in Israel. However, even the mass, admitedly happier within their

own Jewish nation, might wish to erase the blemish of painful. memories.

But this wistful turning to the lovely

scenes of their native lands, their joy in the colorful traditions they

knew in their youth, and the universal, perhaps healthier tendency to prefer

recollection of the sweet moments of life rather than the bitter, should

not obscure the actualities. Many Iraqi or Syrian or North African Jews

have wistful and moving recollections of the streets and the rivers and

the flowers they loved; they long to see Damascus or Cairo or Baghdad again.

But in evaluating the nostalgia, one must remember that there were many

German Jews who had similar memories of Berlin.

This page was produced by Joseph

E. Katz

Middle Eastern Political and Religious

History Analyst

Brooklyn, New York

E-mail

to a friend E-mail

to a friend

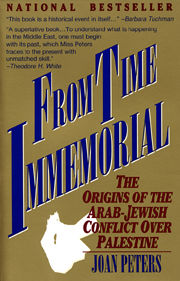

Source: "From Time Immemorial" by Joan

Peters, 1984

SPECIAL

OFFER Purchase this national bestseller available at WorldNetDaily

http://www.shopnetdaily.com/store/item.asp?ITEM_ID=36

|

SPECIAL

OFFER

SPECIAL

OFFER